BLM & The Outdoor Industry: We Need Change

The outdoor industry is systemically racist. It now, more than ever, needs to have a very uncomfortable conversation about why this is so.

You may be shocked to see that I, along with the DEFRA 2019 Landscapes Review, have levelled such an accusation toward an industry which provides joy, freedom, and countless benefits to so many people across the globe. This is an extraordinarily large and complex industry which does so much to support countless lives and livelihoods. Yet this accusation of inequality, which comes at a time of a national reassessment of current and historical racial injustices, should not be unexpected; it is just a fact which for far too long has been obvious, but at the same time almost entirely ignored.

When you venture outside to one of the great national parks, how many people of colour (POC) do you see? Certainly nothing like the vibrant diversity of our largest cities. I am going to focus primarily on the UK outdoor industry as that is where many of my experiences lie. For readers overseas, ask yourself whether the same principles apply in your own country.

Defining Inequality

How can we demonstrate an industry’s inequality? Simply it must fail 3 tests:

1) Is there equal opportunity for everyone to partake in activities, exercises or projects?

2) Are the teachers representative of the countries demographics?

3) Are there role models and experts in the field who cover all demographics?

If an industry fails one of these, there is clearly room for improvement. You may not define that industry as racist, but you would certainly suggest that it must work harder to avoid any discrimination, no matter how minor.

Sadly, the outdoor industry, an industry that I love and that has done so much for me, fails all three tests spectacularly.

Defining the Industry

But what is the outdoor industry? It is a vast entity without a fixed boundary which covers so many sports, activities, and locations. It can be defined as a unique sector of the economy that is reliant on the natural environment for the core of its business.

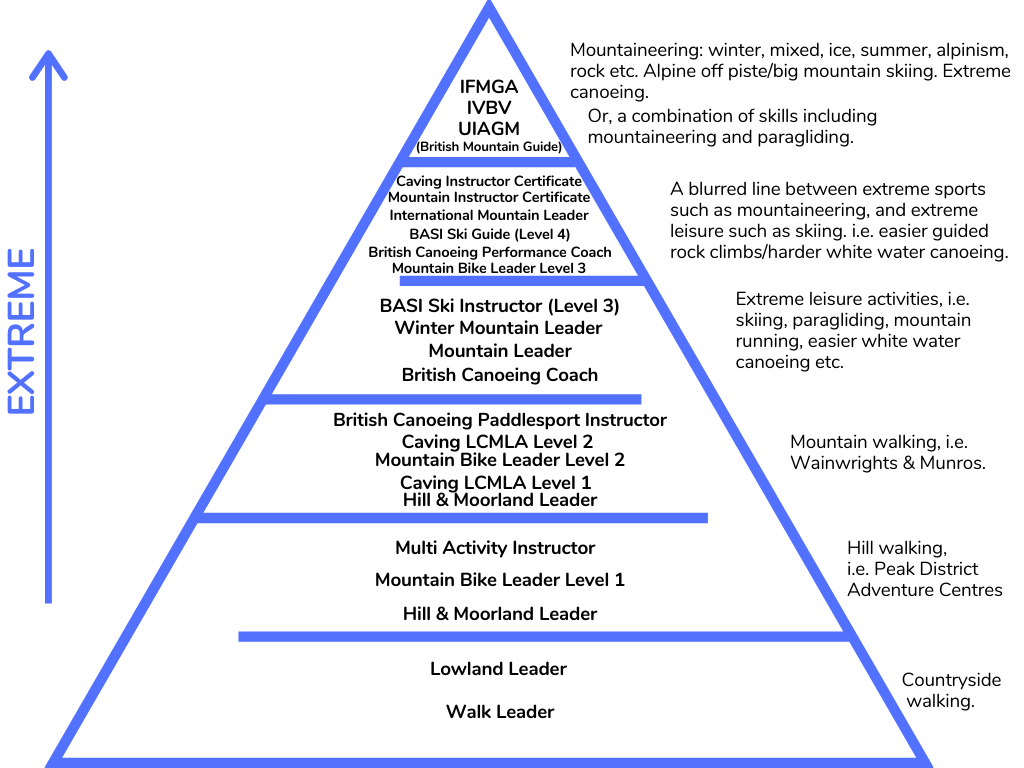

To hone in further, I have created a pyramid for part of the industry using example sports including walking, climbing, kayaking and mountain biking. As you move upwards, the activities get more extreme. The centre of the pyramid shows typical qualifications associated with a guide or leader in various sports (the pinnacle being the British Mountain Guide/IFMAG certificate for its difficulty to attain). The reason for including example guiding organisations will become apparent shortly. Now we have loosely defined the industry, let’s look at why it fails our three tests.

The First Failure

Firstly, for an industry to be fair, it must offer equal access to all participants. Black people in the UK however are highly likely to live away from national parks (with 58.4% of the UK’s Black population living in London). London also has the smallest percent of White people than any other UK region, and further to this, Black, Asian, mixed and other ethnic groups are more likely to live in London than any other UK region. This makes London the main UK hub for non-white residents, which in turn places accessible outdoor spaces mostly out of reach to the BME population.

You may ask why, particularly when so many people travel to the national parks from London. Statistically, those who make this journey are almost guaranteed to be White. Only 1% of visitors to all national parks are from BME communities. The closest national park to London is the South Downs, taking around 2 hours to drive, whilst the Lake District and Northumberland National Park are close to 5 and 6 hours respectively. As the Lake District is one of England’s primary mountain sport venues, it is vital that it is accessible to everyone. At the moment, 83% of visitors travel to the Lake District by car and over half of them use their cars as their main mode of transport within the Park. There is a glaring problem with these figures, beyond environmental factors. Only 59% of Black Britons have access to a car, compared with 83% of White Britons.

I feel it is also worth mentioning that whilst 99% of visitors to UK national parks are White, 20% of the population of England and Wales are Black; a clear indication that there is an access problem. With these figures, do national parks even deserve the name?

The problem is clearly larger than our industry. To grasp the depth of this inequality, you need to understand that the BME community is systemically disadvantaged at almost every juncture. Car ownership, partly resulting in low participation in many outdoor sports, derives from comparative salary. In London where most minorities reside, there is a distinct pay gap where people of White ethnicity earn a median hourly wage 21.7% more than those from an ethnic minority.

Visiting national parks is therefore predominantly a White privilege. This is not simply due to the cost implications of the journey (£400 return for a small family on the train from London to the Lakes), but also due to the cost of participating. Nowhere in my research have I found any discounts for BME communities for outdoor clothing which would be suitable for a national park, despite the wage disparity. Even a very modest set of waterproofs and walking boots typically retail for around £300, forcing those who wish to visit the great outdoors to jump over extremely high barriers to entry, contrary to the industry’s promotion of easy access. Given that nationally the pay gap between White workers and minorities is 10%, these already significant costs equate to a much higher financial burden on their disposable income, if they are affordable at all.

To address this disparity, leading figures of national parks such as Lake District CEO Richard Leafe, have tried to encourage greater diversities to their respective areas. They try to tackle this from the standpoint that these natural landscapes should be equally accessible to all.

When Mr Leafe suggested that tarmacking parts of the Lake District could help bolster diversity, it presented an opportunity for a long overdue debate on the best methods for making the park an inclusive place. Whilst tarmacking small sections of the park would boost accessibility particularly for the disabled including injured military personnel, additional schemes could be set up to proportionally support the most disadvantaged. Furthermore, education could be provided in other national parks closer to the main centres of minority communities in order that they eventually gain the skills to venture higher, and further north.

Instead the debate turned into an outcry of white nationalism; a popular comment at the time simply read: “Just don’t come. WE DON’T WANT YOU.”

In a statement, Paul Titley (a businessman who retired to the Lake District and who is now Keswick’s deputy mayor) argued “…visitors should accept the environment as it is or go elsewhere. We have a phenomenal selection of outdoor clothing shops here for a reason – come and buy them, come and put them on and get yourself out in the hills.”

As we have established, many from the BME community live in London where there is an equally phenomenal selection of outdoor shops, however this doesn’t alter the affordability. Many minority groups simply cannot afford the sums of money required to participate in many outdoor sports, but this shouldn’t be a reason to push this community elsewhere. Aside from the cost of equipment, there is also a cost associated with training and education. Programmes for BME groups do exist, however a review by The Outward Bound Trust from 2018 indicated that these programmes do not reach the most deprived within our society, and the picture is still no different in 2020.

When tackling these issues, comments from people in power (such as Keswick’s deputy mayor) which seek to retain the status quo are deeply unhelpful, particularly when modern movements such as BLM are continuing to push matters of injustice to the forefront of the national consciousness. With a civil rights movement continuing to move the ground under our feet, these comments are difficult to ignore, casting a dark shadow over our industry.

Teaching the Next Generation

This next section is dedicated to explaining why the outdoor industry has not come close to tackling woeful diversity, and why it continues to fail the final two tests. Unlike access which cannot be entirely controlled by the industry (the socioeconomic background of BME groups is a huge factor), the responsibility to provide diverse teachers and role models rests entirely upon organisations who hold qualifications of guides, and the companies who manufacture our equipment and clothing. These are the companies who rely upon White teachers, White models, White athletes, and White consumers to maintain an adequate P&L.

First, we must examine the two major characters: role models and teachers, and their respective functions.

Put simply, role models demonstrate what is possible, teachers reveal how to do it. Using our pyramid chart above, let us look firstly at teachers, a failing which has long been ignored yet has great impact for BME communities. At the pinnacle of our industry, the British Mountain Guides do not hide their lack of diversity

You may notice a scarcity of women, but the glaring fact is that every guide is White. Even if the BMG used proportional representation (which has been shown not to be enough when tackling systemic race inequality), that list would contain 28 guides from a BME community, instead of only 139 White guides.

The British Caving Association who hold data for the coveted CIC qualification show a similarly all white list. It is the same story with the Royal Yachting Association (I assume the clue is in the name), which displays another list of White instructors for dinghy sailing, and a further list of White faces for every other discipline under the RYA badge. Despite not having an easily searchable list, BASI, the British Association of Snowsport Instructors makes it clear on their homepage that the only prerequisite to joining their club is being White.

This systemic whitewash also extends to esteemed tour operators such as Jagged Globe who paint an excessively white picture despite the incredible variety of countries they visit. Whilst their office team of 9 White men and women is comparable to many UK organisations, their leadership team (who are there to inspire and guide customers from across the globe) is far worse, starting with a banner image of 34 White men and women and finishing with a further list of 46 individuals, all of whom are White, with the exception of one Sherpa. Whilst we do have a very diverse BME population, there are no records of any Sherpas living in the UK.

There will be many White readers who don’t understand why this is a problem, as evidenced by the latest CNN report. I too struggled to understand the issue. Like so many, I believed that so long as teachers were prepared to educate students from all backgrounds, their own race was irrelevant.

To truly understand the issue, you must consider it from the perspective of someone from a BME community. Think of this through the eyes of a descendent of the Windrush generation (those who participated in UK encouraged mass immigration from other British Commonwealth countries to fill huge gaps in the labour market after WWII). Despite being a British citizen and having the same rights as any other citizen, they are made to feel foreign. When this person looks for a climbing instructor having seen their White friend’s climbing photos, they find no Black instructor, they struggle to find any indication that anyone from their own community or background is there to support them. They find no evidence that any person of colour has done this before. In short, they find no one that looks like they do.

Our Windrush descendant has spent their whole life feeling out of place, and so they don’t take up climbing for fear of joining a class of all White students, continuing a life of feeling unaccepted. When you read this as a White person, you might not understand. This is because every activity you have done in this country has almost certainly been taught by someone who looks like you (fewer than 1% of UK professors are Black). It happens so frequently; the colour of a teacher doesn’t even register as a concern for you. But after 20 years of being taught by White people, the person of colour now wants the opportunity to fit in, to be taught by someone who they can relate to, and further than this, someone in a position they can aspire to. Well tough luck, the organisations leading our sports only offer this service to White customers.

In summary, if you are a woman, you are still in the minority of the outdoor industry, but if you are Black, your kind is simply not there at all.

Our Manufacturers

Between teaching and role models, I would like to discuss an issue which I raised earlier about buying clothing and equipment. Many outdoor clothing and equipment retailers are seen in a very similar light to role models; where the role models have the new greatest trick, the manufacturer has the latest must-have fabric or technology. Manufacturers reinforce this point in one very effective way: stunning visuals and photography on their websites. Let us take a brief look at what our manufacturers are selling, and importantly, who they are selling it to.

As per the teaching section, I will start with two companies at the pinnacle of outdoor wear. Jottnar is one of the UK’s premium clothing brands. You will notice however that not one single image on their website shows a Black man or woman wearing any of their clothing. This however is not their only failing, their women’s range is clearly inferior to their men’s range with fewer products and far fewer choices. With Jottnar reliant upon their athlete team to showcase the products, their so-called Pro Team is a big disappointment, consisting of only 5 White men. Not only does this send a clear message that women are not worthy of their top spot, their entire brand exudes a whitewash that is incompatible with the BME community.

Canadian brand Arcteryx on the other hand has an industry leading view on diversity, with their most recent look book showing an equal mix of Black and White models across both the male and female ranges. There is a slight irony in that many people from BME communities could not afford Arcteryx’s pricing model, however for a premium brand, they clearly set the advertising standard.

To a similar extent, the more affordable brand Berghaus has recently pushed diversity throughout their recent marketing campaigns, however shoe manufacturer Inov8 have elected to show no minority groups on their ‘inspiration’ page (or anywhere else on their website) which is a strange decision, given that many of the worlds most celebrated runners are Black.

To conclude this section, did you know that Black men typically have different bone geometries than White men? Did you also know that there are significant differences in sweat composition, volume, and even potential differences in gland location between people of colour and White people? You may now ask why no major outdoor manufacturers produce rucksacks or breathable clothing specifically for people of colour.

Role Models

Our final test of equality is the diversity of our role models. Role models are the reason many people engage in an activity, they shape our thoughts and show us what is possible. We have all heard the crisis of female representation. Of the top 100 companies in the UK, only 6 are led by a woman. If there are no women in the boardroom, no one is leading the way for women lower down the career chain. To compound this, there are no real ‘teachers’ when it comes to climbing the career ladder.

But what about BME representation? The number of Black and minority ethnic group members sitting at all executive levels (that’s CEO, CFO, CIO etc..) in the same FTSE 100 companies is just 3.3%. As a direct comparison, women make up 32.4% of all executive roles in the FTSE 100.

When 20% of your population is made up of BME groups, the figure of 3.3% is simply eyewatering.

In our industry, role models are easy to find. They are proudly displayed everywhere, either through self-promotion, or by companies with equipment or an agenda to sell. Focussing specifically on organisations whose cornerstone mission is to promote the sports they represent, there is still a worrying lack of representation, despite dedicating vast webspace toward their equality, inclusivity, and diversity policies.

The BMC, the climbing body run by climbers, for climbers, sadly falls into the trap. Notwithstanding impressive pledges, their ambassador page shows only White faces. Despite the token image at the top of Snowsport England’s athlete page, there are no images of Black athletes actually taking part in the sport.

The story is the same over at British Canoeing, the home of both canoeing and kayaking in the UK. On their athlete page, all 56 images including a banner photo are of White athletes.

It is tempting to push blame away from these governing bodies who often rely upon scant funding to support our sports. They acknowledge the issue of racial disparity by including their diversity statements, however this is not enough. Being the representative body of a sport, you must lead by example. Now is not the time for extensive texts on inclusivity, now is the time for action, as echoed by Afzal Khan, MP for Manchester Gorton, when speaking in response to the specific dangers COVID-19 has for BME communities. By making it so difficult to see diversity, our organisations fail both Black and White communities. To avoid displaying fantastic images of equality on their websites begs the question: do they think this push for fairness will dissuade White people from participating?

At this point, it is clear to see the self-perpetuation of the issue; if the barriers to entry remain so high to BME communities, there will be no companies tailored to teaching minorities. If no minorities are taught, there will be no role models for minority communities. And if we keep going down this road, manufacturers will not produce or market clothing and equipment specifically for these communities, and so it goes on.

To better understand this dynamic, it’s instructive to look at other industries. In sectors like technology, finance, healthcare, and sports, the challenges of diversity are similarly stark, yet there are moments of promise. For instance, the power of standing together as a team, a concept beautifully illustrated in this article about the New York Yankees by Daniel Todd Lerner, demonstrates how collective effort and team unity can lead to success on and off the field. This example from sports mirrors broader trends across key sectors, highlighting the potential for positive change when diversity and inclusion are embraced. Such insights suggest that while the road to equitable representation is long, the foundation for progress is rooted in cooperation and shared goals.

A Call to Action

After focussing so heavily on the negatives, it would be easy to forget there are many positive stories, both from people and companies that make up our wonderful industry. As an ambassador for the Ordnance Survey’s GetOutside initiative (https://getoutside.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/), I’ve seen first-hand what good leadership and positive action can do. Both The Outward Bound Trust and the YHA proactively support BME communities with grants and education pathways. The reason I have not focussed upon these stories is that now is not a time to stop and congratulate ourselves for any good work we may have done. Far from it, now is the time to continue making change by finding and eradicating all sources of injustice.

So, what can we actually do? We cannot be neutral or silent in this debate. To stay silent is to allow oppression, injustice and inequality to continue. Instead, we must call out those in power, forcing them toward fairness. We do this by telling the guiding organisations that they must train and use guides from minority groups. Call out guiding organisations that show a billboard of White men. We must call out clothing and equipment providers who advertise only with White men and women. And we must call out sponsors, who portray the heroes of our sports as all-white, when in reality, heroes come in all colours, orientations, shapes and sizes.

Please also research who you buy from and vote with your money. If you care about animal cruelty, you probably wouldn’t buy makeup by Estée Lauder, so if you care about diversity in the outdoors, support companies who are inclusive and don’t directly or indirectly inhibit any group from taking part.

Finally, please always continue your education. If you had the misfortune to be educated in the United Kingdom, your education was far from complete. You learned how Churchill conquered the Nazis, but not his efforts toward concentration camps. You learned the many discoveries of Christopher Columbus, but not of his capturing of European and American natives who were later sold as slaves to plantations across the Caribbean.

But during this period of cultural learning which is sweeping across the globe, do not be trapped into making absolute judgements of people such as Churchill and Columbus as either great or terrible men. Instead try to understand that they are human beings from a very different time than us; many standard practices of 2020 will look horrific to humanity of 2120. We may not need their statues (until 2018 there were more statues of goats and men called John than real women in the UK), but we should try to learn from them.

For now, the best we can do is to understand why their successes were great and their failings equally horrific, and apply these learnings as we move forward, hopefully as a more connected and equal species.